While the roman military structure is widely known the political institutions behind Rome’s success often remain a mystery. Today I would like to give an overview of the political offices & institutions of the roman republic.

The main political institutions of the roman republic were the senate (with the offices of Quaestor, Aedile, Praetor, Consul, and Censor), the comitia centuriata (army assembly), comitia plebis, comitia tributa, and the comitia curiata. While the system in parts appeared like a democracy it was controlled by the upper class since they united the majority of the votes on them. As long as the upper class voted uniformly the majority of Roman citizens had no chance of influencing the state politics.

At first, I will focus on the different public offices that senators would hold before I will dive into the different political institutions of the roman republic and how they interacted.

Let`s find out more.

The cursus Honorum – how to become a roman politician

The cursus honorum was a sequence of public offices that a politician had to follow to one day become consul.

The lex villa annales in 180 BC fixated the sequence in which the offices of the cursus honorum had to be held, the minimum age for an office, and the 2-year interval between two offices.

Before 180 BC BC offices could be skipped. To even enter the cursus honorum several requirements had to be met.

Until 153 BC the new magistrates would take office Ides of March (March 15), after 153 BC at the 1. Of January.

Minimum ages of every roman public office

Quaestor: at least 30 years old

Aedile: at least 37 years old

Praetor: at least 40 years old

Consul: at least 43 years old

Censor: the end of a political career, usually a few years after having served as consul.

Please note that these age requirements were only introduced by the lex villa annales in 180 BC. Before that, there were no age requirements.

But to be able to run for the office of Quaestor you also had to meet some other requirements aside from being old enough.

Requirements for starting a political career

In order to start a political career, a candidate had to have served 10 years of military service. Now since the Roman army during the time of the republic was not a standing army that requirement meant that the candidate had to partake at a certain amount of campaigns instead of serving a consecutive time of 10 years.

After the lex villa annales in 180 BC, a man had to be at least 30 years old to run for quaestor (the first office on the cursus honorum). Apart from being a roman citizen a certain amount of wealth was also necessary since none of the political offices paid any kind of wage.

That, by the way, limited the potential candidates for a political office to the social class of Equites (=knights). There was actually only one difference between Senators and Equites. More on that here.

Most roman citizens just didn`t have the money or the connections necessary for a successful political career.

Now you might ask why one would pursue a political career when there was no pay involved.

Benefits of pursuing a career in roman politics

While roman politicians did not get direct pay the higher-ranking politicians (consul & praetor) would get a province to govern after their term had ended. And governing a province didn`t only open up the possibility of gaining military glory but could also be highly profitable.

The famous roman writer and lawyer Marcus Tullius Cicero actually based a good portion of his reputation on a case where he represented the inhabitants of a Roman province in court.

The governor of that province of Sicily, a certain Verres, had plundered his province with such thoroughness that he was sentenced fort hat. That by the way resulted in one of Cicero’s most famous speeches. If you are interested in reading it (don`t worry, it has been translated from Latin into English) you can get the booklet here on Amazon.

Another nice side effect of getting a province was the possibility of waging a war. Since the governing roman politician commanded the troops that were present in the province there was the opportunity for a decisive victory. And there were plenty of opportunities during the expansion of the roman republic, more on that here.

And such a decisive victory was the precondition for being granted a triumph through Rome. More on why a triumph was so desirable for roman politicians in my article here.

Basic principles of all political offices

Rome was rightfully afraid of a singular man accumulating too much political power in his hands and overthrowing the republic. To prevent that from happening 5 principles were developed.

The principles of annuity, collegiality, and the prohibition of Iteration, Continuation, and Cumulation all had the goal to keep individual men from concentrating too much power in their hands and becoming a threat to the political system of the roman republic.

- Principle of annuity: Roman magistrates during the roman republic could only hold the respective office for one year

- Principle of collegiality: Public offices of the roman republic were split among several men. There were for example always two consuls

- Prohibition of Cumulation: Politicians were not allowed to hold more than one political office at a time. So if you were consul you could not also be a praetor

- Prohibition of Continuation: Politicians were not allowed to hold a political office multiple years in a row

- Prohibition of Iteration: The prohibition of Iteration kept politicians during the roman republic from holding the same office multiple times. In the later years of the roman republic, the prohibition of Iteration was lifted for the office of Consul.

It wasn`t until the very late republic that these principles were permanently breached. Until then they worked (at least most of the time). These principles provided stability to the political system of Rome and were the main reason for why Rome was so successful.

Public offices of the Cursus Honorum

As already mentioned. After the lex villa annales in 180 BC, the offices within cursus honorum had to be absolved in a certain order. A man would start on the lowest level with the least power and would climb through the ranks to the most powerful offices.

A major benefit of the cursus honorum was that young men were forced to gain experience in offices that dealt with less important matters before they could hold offices where they actually had to command armies or make decisive decisions.

I mean let’s face it. An incompetent Quaestor who was basically a glorified accountant could do a lot less damage than an incompetent consul who had to command an army.

Let`s now check out the different offices of the cursus honorum in chronological order.

Quaestor

After at least 10 years of military service (as already mentioned on top) a man would run for the office of quaestor.

Quaestors were responsible for financial management and were secretaries. They could either be assigned to a position in Rome or a Consul/Praetor outside of Rome. Serving a full year as quaestor was the requirement for a lifelong seat in the senate. After 180 BC Quaestors had to be at least 30 years old.

The tasks of a quaestor varied depending on if he was used inside of Rome or deployed to assist a Consul/Praetor.

It is not entirely clear how many Quaestors would exist simultaneously.

But it is assumed that there might have been 10-12 Quaestors until Sulla raised the number to 20. Caius Julius Caesar then raised the number of Quaestors to 40 while Augustus reduced the number back to 20.

Tasks of a Quaestor in Rome

Within Rome, Quaestors were tasked with the management of the Aerarium (the treasury that was housed in the Temple of Saturn and the state archive.

By the way. Managing didn`t mean doing it himself but overseeing specially trained slaves or freed slaves doing the actual work. Please check out my article here for more information.

Tasks of a Quaestor deployed outside of Rome

While the tasks of a Quaestor who was stationed inside of Rome were pretty boring the tasks outside of Rome could be much more exciting.

When a Quaestor was assigned to accompany a magistrate with the imperium (either a consul or a praetor) he was usually tasked with the financial management of the province, being the stand-in of the consul/praetor, or being purser while also being responsible for supplying the army on campaign.

Aedile

While a Questor could be assigned to a position outside of Rome the Aediles had to stay in Rome.

There was a total of 4 Aediles, two of them of plebeian descent (so-called plebeian aediles) and two of either plebeian or patrician descent (so-called aediles curules). These men had to be at least 37 years old and were tasked with maintaining the public order, the supply of food & drinking water, and the organization of Gladiator games.

Interestingly even after 180 BC, the office of Aedile was actually not mandatory.

Technically a man could run for the office of Praetor without having served as Aedile. But since all public officials were voted by the people of Rome (more on that later) running for Praetor without having served as Aedile was an exercise in uselessness.

The reason for that was that among other duties the Aediles were also responsible for hosting Gladiatorial games, more on how a day of Gladiatorial games worked here.

While the purpose of Gladiator fights was originally not to entertain the crowd they became a sure way to gain popularity among the voters during the roman republic. Please check out my article here for more information on why Gladiators fought and how their motives changed over time.

Tasks of the roman Aediles

The tasks of the Aediles were summed up in the cura urbis (= taking care of the city). The Aediles had to take care of security, infrastructure, and cleanliness within Rome.

That included but wasn`t limited to overseeing the markets, the supply of Rome with groceries and drinking water, but also several welfare programs for the roman poor.

It was actually one of the less well-known effects of the expansion of the roman republic that the middle class shrank while the lower class exploded. Please check out my article here to find out why.

Apart from that, the Aediles were also tasked with supervising measures to increase security within the city and the already mentioned hosting of public gladiatorial games and other dispersions.

These games were actually one of the reasons why only men from rich families, so-called Equites (more on the different roman social classes here), since it took an enormous amount of money to actually pay for these public games.

Let`s just take Caius Julius Caesar. He actually equipped his Gladiators with silver armor to make them more impressive. Impressive indeed, but also costly! More on that and why Caesar held Gladiator Games to honor his deceased father decades after his death in my article here.

The next step in climbing the political pyramid was getting voted into the office of Praetor. And while all the other offices until Praetor didn`t offer a possibility to get rich (small bribes aside) that changed with the office of Praetor.

Praetor

The office of Praetor was the second-highest of the political offices during the roman republic.

Not only did the Praetor possess the Imperium but also the minor potestas (= a lower type of official authority than the consul). That meant that the Praetor could command armies.

Originally there were only two Praetors per year. One is the praetor Urbanus who would administer justice among Roman citizens and the praetor peregrinus who would administer justice among non-roman citizens. In 227 BC the number of Praetors was raised to 4 and in 197 BC to 6.

The increase in Praetors is closely connected to the expansion of the roman republic, more on that expansion here. When the Praetors (apart from the praetor urbanus and the praetor peregrinus) were not needed to command armies they would be sent to the provinces to act as governors. More on the different provinces and when they were installed here.

Tasks of a roman praetor

As mentioned. The Praetors possessed both the Imperium (=Power) and the minor potestas (=authority, but to a smaller degree than a consul).

The imperium gave the praetor official authority while the potestas minor gave him legal power over the other public officials. In return, the minor potestas of the praetors was trumped by the potestas major of the consuls.

Generally, a praetor could be tasked with taking command over an army, taking a position as provincial governor, introducing bills into the assembly (more on that later), and holding legal functions. As mentioned: These legal functions can be separated into the position of Praetor urbanus and praetor peregrinus.

When a Praetor would command an army or be assigned to a province as a governor he would be accompanied by a quaestor who would relieve and sometimes represent him.

One of the benefits of being Praetor assigned to govern a province (or a former praetor who after serving his year would usually get a province to govern for one year) was that that position as governor offered him countless opportunities to enrich himself.

Either by corruption or by plundering the province with brute strength (Here the Imperium, the qualification to lead an army came in handy).

A good example of a former praetor who overdid it when it comes to plundering his province is Caius Verres.

After Verres had served his year as Praetor Urbanus in 74 BC he got assigned to govern the province of Sicily as propraetor. He used his office to enrich himself to a level that the inhabitants of Sicily (represented by a certain Marcus Tullius Cicero) were able to prosecute him in front of a roman court.

The indictment that Cicero held during that process was actually preserved and translated into English. If you are interested you can find the booklet here on Amazon. When I was in school we actually had to translate passages of the speech, so I can highly recommend it!

Now I have mentioned that the potestas minor of the praetor was lower than the potestas major of the consul.

So let’s take a look at the highest and most powerful regular office that the roman republic had to offer!

Consul

The Consul was the highest and most powerful regular office during the roman republic although the two Consuls could not just rule on their own but had to coordinate with the senate. More on that under the Heading Political institutions of the roman republic.

The office was also one of the oldest offices and is rooted in the origins of the roman republic. Do you want to find out more about the shocking incident that drove the Romans to overthrow their king and install a republic? Here you can find answers!

The Consuls, both plebeians and patricians could hold the office, did not only possess the Imperium militia and domi (authority in domestic & foreign affairs) but also the potestas major giving them more legal power than any other public official. Additionally, they had the auspicum, the duty to take the necessary steps to maintain the pax deorum (=peace of the gods).

Interestingly the prohibition of Iteration was lifted for the office of Consul. Probably to enable especially capable men to serve more than just one year.

It is also noteworthy that the circle of families that supplied Rome with Consuls was rather small. Just a few examples: In the time from 366 to 44 BC the family of the Cornelia Gens provided Rome with 63 Consuls, the family of the Fabier Gens 32.

After a consul had served his year of office he would be installed as a provincial governor for one or multiple years holding the title of Proconsul. The choice over what consul would get what province was actually up to the senate. And the senate used that privilege to ensure that the consuls would work together with the senate. More on that later.

If a consul did not honor the senate and its advice he could easily get a less valuable province where neither military glory nor fortune could be expected. Other more cooperative consuls could expect more valuable provinces.

But to be given command over a province the consuls had to serve their year of service first. Let`s look at the tasks a consul had.

Tasks of the Consul in Domestic politics

When it came to domestic politics the consul’s tasks partially overlapped with the ones of the praetors.

The consuls had the right to introduce legislative initiatives into the assembly, they would direct meetings of both the Comitia Centuriata and the senate, perform representative duties, and exercise their legal authority.

Now I just mentioned the assembly and the comitia centuriata but didn`t explain their significance or what they were. But I will catch up on that in the paragraph political institutions of the roman republic.

Tasks of the Consul in Military & foreign policy

Since the Imperium came with the office, the Consuls would also command armies on campaigns. It is actually assumed that a major reason for the creation of the office of Praetor was to establish a replacement for the case that both Consuls were commanding an army away from Rome.

That alone should be a good indication of how important the Consuls were on a military level.

When it came to foreign politics and the military the Consuls would not only represent the roman republic as a whole but would also welcome foreign legations.

Maintaining the pax deorum

While the term pax deorum in English is generally translated with peace of the gods the actual meaning is much more complex.

The pax deorum was basically seen as a bargain between the human and divine world. In return for the correct performance of religious rites like sacrifices, the Gods would not get angry and punish Rome and its people.

Taking the risk of upsetting the gods had to be avoided at any cost to insure a favorable future for Rome. So watching over the correct performance of religious customs and rites was actually incredibly important!

Censor

The office of the Censor was actually an office with a great reputation but no real power. While a Praetor or Consul had the imperium that allowed them to command armies, the Censor didn`t. He also wouldn’t get a province to govern after the end of his term.

That is probably one of the reasons why many of the famous Romans like Pompey, Caesar, and many more never strived for the office of Censor.

Usually, the office of Censor was seen as the closure of a political career. While the office came with a high reputation it would often only be manned every five years and had limited duties, most importantly the census and the lectio senatus.

Let`s look at the census and the lectio senatus separately.

Census

One of the major duties of the censors was to appraise the military potential of the roman population for further expanding the roman influence.

The census is a procedure in which the censor and his assistants appraise the assets of the Roman citizens. That asset appraisal was then used to organize the roman citizens into brackets according to their assets and to get an overview of Rome’s military potential.

That organization in brackets goes back to the military of early Rome where only rich citizens could serve as Hoplites in the Roman army. More on the Hoplites here.

By organizing the citizens into brackets the censors could get a good overview of the male population that could be drafted for the campaigns. More on how the early roman military worked and why the expansion of the roman republic led to an existential crisis in my article here.

The entire procedure of the asset appraisal that was held on the Field of Mars in Rome was ended with a cleansing sacrifice.

Lectio senatus

The second major duty was to keep an eye on the list of senators.

Membership within the roman senate would last a lifetime. But Senators who had stood out with immoral behavior (the bar was pretty high for that) or massive amounts of debts could be expelled by the Censors.

That actually happened, the social permeability that played a huge part in Rome’s success, more on that here, was not a one-way street. Not only social ascent but also social descent were quite common in Rome.

Especially since Senators, Equites, and ordinary roman citizens only differed in one point. More on that one difference between these 3 social classes here.

Tribunes of the plebs (= tribunus plebis)

The office of Tribunes of the plebs was an incredibly powerful office that over time contribute to the drainage of power from the magistrates into the hands of the senate.

The 10 Tribunes of the plebs were sacrosanct. They were tasked with directing the Concilium plebis where they could also introduce legislative initiatives. After the Lex Hortensia of 287 BC, decisions of the Concilium plebis had legal force. Tribunes also had the right of intercessio, they could veto the decisions of any magistrate, even a consul.

Since tribunes were usually young men one might ask if it was really that smart to give that kind of power into inexperienced hands. But it turned out that there were safeguards in place.

The large number of 10 simultaneously serving tribunes ensured that the power the office held was splintered. If one tribune was too ambitious it was easy for the senate to find another tribune to incise against his stubborn colleague.

Because of that scatteredness of the actual power of the tribunes the office of tribune of the plebs turned into a political instrument that could easily be used by the senate and the magistrates.

Famous Tribunes of the plebs were the brothers Caius & Tiberius Gracchus. Both would become heroes of the people after being murdered for their radical reform attempts.

Both had tried to force reforms that would have benefited the roman middle class, the small farmers and craftsmen, who had massively suffered under the expansion of the roman republic, more on that here.

Dictator

While today the word dictator has a negative connotation that was not always the case.

During the roman republic Dictator was an emergency office with full authority in all matters but a limited duration of a maximum of 6 months. After laying down the office the former dictator could not be prosecuted for anything he did while exercising the office.

Since the office of Dictator had such a extend of power the office was only manned in matters of extreme emergency and only by men who were known to be both competent and righteous.

The cases in which a dictator was named had one thing in common. An immediate threat. A time with several dictators was actually the time of the Punic Wars since these wars brought Rome to the edge of total disaster on several occasions. More on the Punic Wars and how they changed Rome in my article here.

The Dictator would have a second in command called magister equitum (= leader of the cavalry) that he would choose from the ranks of former consuls.

It is important to emphasize that until the first century BC the office of Dictator worked well! The Dictators of that time would return their powers to the senate as soon as their 6 months were over or the threat had passed.

It wasn`t until the late republic that that changed opening the way for dictators like Sulla and Caesar who had no intentions of returning their office after 6 months.

Speaking of Caesar. Have you ever wondered why Julius Caesar would rather try to stay dictator for a lifetime than be appointed king? You can find the answer here in my article.

Political institutions of the roman republic

The main political institutions of the roman republic were the senate, the comitia curiata (only gathered on rare occasions), the comitia tributa (assembly organized into tribes and capable of voting lower magistrates), the comitia centuriata (determining assembly until 241 BC), and the Concilium plebis.

Let`s check them out separately!

Comitia centuriata

The comitia centuriata, the army assembly, was an assembly of all Roman citizens and was introduced by the servian constitution in 509 BC after the roman kings had been driven out of Rome, more on that here.

After 241 BC measurements were taken to increase the importance of the 4 lower census classes and to make the comitia centuriata less aristocratic. But these reforms were reversed during the dictatorship of Sulla from 82 to 80 BC.

Just like the Comitia plebis the Comitia centuriata could not act on its own initiative but had to be summoned on the initiative of a magistrate or the Senate.

Composition of the Comitia centuriata (=Army assembly)

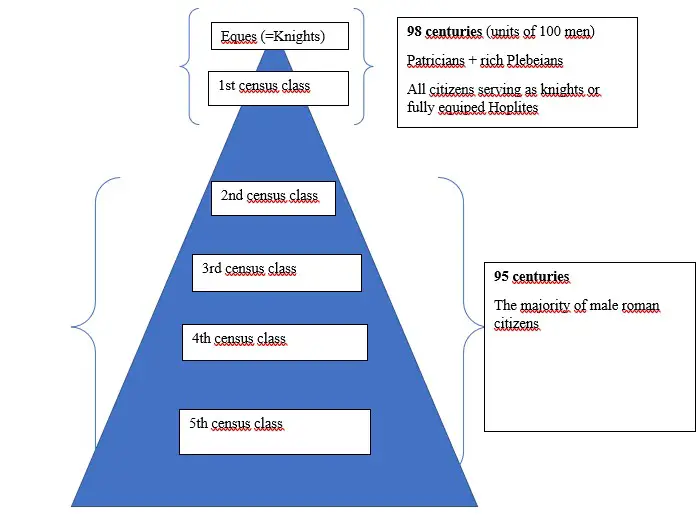

The Comitia Centuriata was presided by a magistrate and consisted of a total of 193 Centuries, units of a hundred men, that were arranged hierarchically. Every centurie had one vote.

The Eques and the first census class, basically all citizens rich enough to serve as Hoplites, made up the 98 Centuries and were allowed to vote first. The other 4 census classes making up 95 Centuries and containing all citizens not rich enough to serve as Holites, voted second.

Since the upper class voted first and the vote was stopped as soon as a simple majority (97 votes) was accumulated the majority of the Roman citizens (organized in 95 centuries) did not get to vote as long as the upper class (organized in 98 centuries) would vote uniformly.

We will dive deeper into the process of how voting for a new law went down and why the comitia centuriata was so decisive during the vote in the last paragraph of the article!

Because of that, the roman republic can be rightfully seen as a res publica, but not as a democracy. The roman republic was a so-called timocracy, a political organization that distributed political rights according to wealth.

Diagram of the Comitia centuriata

Origins of the classification into different census classes

By the way, the reason why not only Equites (the men rich enough to fight on horseback, more on them here but also the men wealthy enough to serve as Hoplites can be found in the way early Rome fought.

Originally only aristocrats and their followers had served in the military. But during the 6th century, BC Rome adopted the warrior type of Hoplite and the fighting style of the phalanx that had both been developed in Greece.

That new way to fight needed more soldiers and since the equipment of Hoplite was expensive that opened the doors for political participation to the group of rich but non-aristocratic roman citizens.

You can find out more about the Hoplites here, how the Phalanx worked here, and how the roman expansion and the use of militias reduced Romans middle class here.

Comitia plebis

The Comitia plebis was presided by a tribune of the plebs, was arranged by tribe, and could also vote on laws.

Following the year 241 BC, the Comitia plebis consisted of 35 tribes, 4 urban roman tribes, and 31 rural tribes of citizens living outside the city of Rome. Since the time of the Gracchus brothers, both the office of tribune of the plebis and the comitia plebis had huge power.

The 35 tribes were not based on kinship or ethnic identity but geographical areas. Every tribe had one voice and contrary to the comitia centuriata the vote would not be ended as soon as an absolute majority was reached making the comitia plebis the more democratic institution of the two.

But since the aristocratic large landowners also controlled the majority of the votes through their clientele structures these aristocrats were also setting the tone in the Comitia plebis.

In general, it is important to say that as long as the upper class was unified it was irrelevant if a draft law was introduced in the comitia centuriata or the comitia plebis.

Only when the upper class was divided on a subject did the roman people actually play a decisive role. Because of that, it is easy to see that the biggest instrument of the upper class for maintaining their power was their unity!

It was extremely rare that the decision that was made by the senate was turned down in the assemblies. One of the rare occasions was the decision for entering the second Macedonian war. After Rome had just won a costly war the people were not eager on entering a new costly war and voted down the decision of the Senate.

Well at least during the first vote. It took a highly patriotic speech to finally convince the assembly to agree on the war against Macedonia. Please check out my article here if you are interested in the Second Macedonian War and the expansion of the roman republic as a whole.

So in general it is important to note that during the middle of the roman republic the roman people only had an affirmative role!

Comitia tributa

The Comitia tributa was an assembly of Roman citizens that was organized according to the tribes. In that context, the tribe does not mean an organization because of kinship but because of geographical areas just like in the comitia plebis.

The Comitia tributa decided on bills and voted for the lower magistrates like Quaestors and Aediles.

Comitia curiata

The Comitia Curiata was an assembly exclusive to Patricians that only rarely gathered during the roman republic. The Comitia curiata likely is the oldest of the Roman assemblies.

It is possible that during the time of the Roman kings, more on that here, the comitia curiata inaugurated the new kings and decided on disputes about inheritances.

It seems likely that during the early roman republic, more on why the roman kingship ended and the roman republic was installed here, the comitia curiata was responsible for making important political decisions.

Most likely the comitia curiata lost its position during the Conflict of the Orders (400-287 BC) when wealthy plebeians demanded a say in political matters for their military services.

During the high phase of the roman republic (287/264-133 BC) the comitia curiata only had sacred duties for which it was led by the pontifex Maximus. During the late roman republic, the comitia curiata basically disappeared.

Senate

The senate is probably the best-known political institution of the roman republic.

The senate consisted of all men who had at least served as Quaestor and had not been expelled by the Censors. Depending on the period the senate consisted of 300 to 1000 members but was dominated by around 30 men who had served as Consuls or Censors and had the highest authority. About 2/3 of the senators didn`t even make it to Praetor.

It is noteworthy that until Sulla raised the number of Senators to 600 to reward his loyal followers the Senate was much smaller. Caius Julius Caesar, more on him here, did the same thing by inflating the Senate to 1000 members.

The senate itself did not have the power to decide on a law. It could discuss the proposals but for a law to be passed, it had to be presented to the comitia centuriata by a magistrate.

Tasks & rights of the senate

The senate was the political control center of the roman republic. All bills either directly or indirectly came from the senate.

The senate mostly influenced roman politics with its auctoritas (=a political weight that was based on tradition, not law) and the auctoritas senatus (meaning that the collective expressions of will by the senate had to be seen as authoritative).

But when it came to the tasks and rights of the senate that institution was more limited than one might think. The senate had the following rights…

- Discussing bills: The Senate could discuss bills but could not take legislative initiatives since bringing these bills into the comitia centuriata was the privilege of the magistrates and tribunes of the plebis.

- Advising the magistrates: the senatus consulta (=instructions based on the auctoritas senatus) meant that the senate had the right to advise the magistrates.

- Determining the provincia of the Magistrate: By having the right to determine what provincia (=sphere of influence) a magistrate would get after his year of service the senate could ensure that its advice was implemented by the magistrates. Not implementing the advice of the senate would have meant that the rebellious magistrate would have upset the entire senate. And that was basically the end of a political career.

- Welcoming and sending embassies

- Prerogative in matters of foreign policies and decisions on war or peace

So one could say that while the Senate did not directly control all political aspects of the roman republic it sure indirectly controlled the magistrates and made sure that its „advice “ was implemented in the politics of these magistrates.

And that now brings us to the last topic of the political system of the roman republic. How were laws decided?

How were Laws decided during the roman republic?

Step 1: A bill is initiated in the senate (either by a senator or a magistrate)

- The bill is then discussed and a consensus would be found

Step 2: The magistrate „ex auctoritas senatus“ (= by the dignity/influence of the senate) brings the bill to the assembly

- usually to the comitia centuriata, on some occasions to the comitia plebis. The reason why the comitia centuriata was preferred is that due to the already mentioned course of the vote (please compare the paragraph „comitia centuriata“) it was easier to pass the bill as long as the upper class was united behind that bill.

Step 3: The comitia centuriata would vote on the bill

- since the upper class held the majority of the votes the bill would pass as long as the upper class stood behind the bill

Step 4: The lex (=law) would be named after the senator/magistrate that initiated the bill and become legally binding

- The already mentioned lex Hortensia (that in 287 BC ended the Conflict of the Orders and designed the presented system of Government) was initiated by the dictator Quintus Hortensius

I hope you enjoyed our trip to the roman republic just as much as I did. Please also feel free to check out our other articles like for example the one answering the question of why Athens and Sparta were rivals here.

Take care of yourself because you deserve it. You really do.

Until next time

Yours truly

Luke Reitzer

Source

A. Heuß, G. Mann (Hrsg.); Propyläen Weltgeschichte. Eine Universalgeschichte, Band IV Rom – Die Römische Welt (Frankfurt a. Main 1986).